Dying Declaration Crucial in Affirming Conviction; Compensation Directed for Victim's Family

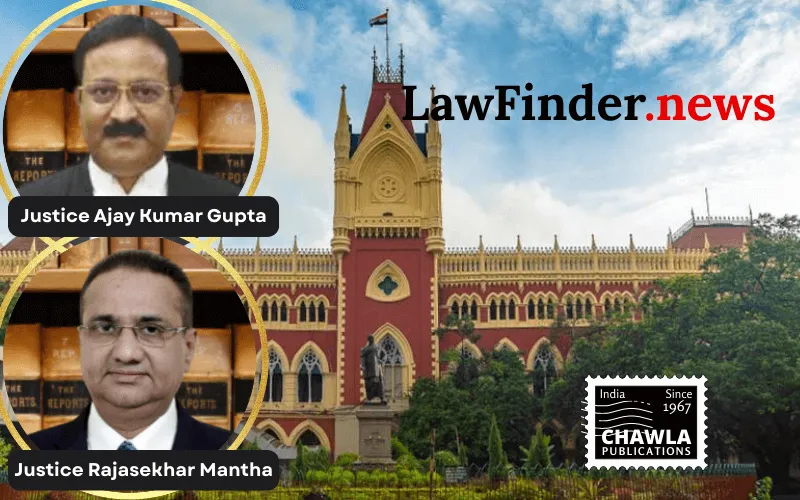

In a significant judgment delivered on January 19, 2026, the Calcutta High Court's Division Bench, comprising Justices Rajasekhar Mantha and Ajay Kumar Gupta, upheld the life imprisonment sentence handed down to Sajal Kanti Roy @ Subrata @ Subho and another appellant for the murder of Sagar Ghosh during the Panchayat elections in West Bengal in 2013. The appellants, affiliated with the ruling party, were convicted under Sections 302/34 and 448 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), and Section 27 of the Arms Act, after the victim's dying declaration and corroborative evidence pointed to their involvement in the murder.

The case unfolded in the tense atmosphere surrounding the Panchayat elections, where political rivalry led to the fatal shooting of Sagar Ghosh at his residence. The victim's son, contesting as an independent candidate against the ruling party, allegedly prompted the attack. The spontaneous naming of his assailants by the victim after he was shot played a pivotal role in affirming the conviction. The court ruled that the victim's statements were admissible as dying declarations under Sections 6, 7, and 32 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

The High Court emphasized the reliability of the dying declaration, noting its immediacy and the victim's conscious state despite the pain. It rejected claims that the victim was unable to see his attackers due to poor lighting, stating that the ability of assailants to accurately target the victim indicated sufficient visibility. The judgment underscored the doctrine of necessity in admitting dying declarations to prevent culprits from escaping justice.

Further, the court ordered the appellants to pay a fine of Rs. 1,00,000 each, which would be distributed equally between the victim's wife and daughter-in-law as compensation. In case of default, the State was directed to compensate the family with Rs. 5 lakhs. The judgment modified the trial court's order regarding compensation distribution and mandated recovery procedures under applicable laws.

This verdict marks a closure in a case marred by procedural delays and irregularities during investigation, including coercion claims by the victim's family and contested FIR records. The judgment reinforces the judiciary's reliance on direct witness accounts and dying declarations, even amidst investigative shortcomings.

Bottom Line:

Dying declaration of the victim admissible under Section 6 and Section 32 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 - The spontaneous naming of assailants by the victim after being shot constitutes part of the same transaction and indicates the cause of death.

**Statutory provision(s):** Sections 6, 7, 32 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872; Sections 302, 34, 448 of IPC; Section 27 of the Arms Act; Section 313 and 164 of CrPC.